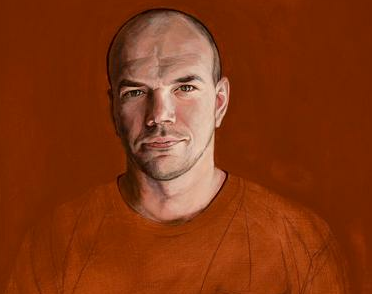

Tim

DeChristopher, the climate activist jailed by the Obama administration

for disrupting a last-minute Bush administration oil auction, finds his

strength by accepting the terrible reality of climate change.

Tim

DeChristopher, the climate activist jailed by the Obama administration

for disrupting a last-minute Bush administration oil auction, finds his

strength by accepting the terrible reality of climate change.

In an interview recorded in May 2011 before his two-year jail term began in July of that year, DeChristopher told environmental activist and author Terry Tempest Williams that he was willing to be Bidder 70 at the Bureau of Land Management auction in Utah – willing to dedicate his life to fighting global warming through nonviolent direct action – the moment he learned that the window had already closed for humanity to avoid all of the terrible catastrophes of climate pollution:

TIM: I think part of what empowered me to take that leap and have that insecurity was that I already felt that insecurity. I didn’t know what my future was going to be. My future was already lost.

TERRY: Coming out of college?

TIM: No. Realizing how fucked we are in our future.

TERRY: In terms of climate change.

TIM: Yeah. I met Terry Root, one of the lead authors of the IPCC report, at the Stegner Symposium at the University of Utah. She presented all the IPCC data, and I went up to her afterwards and said, “That graph that you showed, with the possible emission scenarios in the twenty-first century? It looked like the best case was that carbon peaked around 2030 and started coming back down.” She said, “Yeah, that’s right.” And I said, “But didn’t the report that you guys just put out say that if we didn’t peak by 2015 and then start coming back down that we were pretty much all screwed, and we wouldn’t even recognize the planet?” And she said, “Yeah, that’s right.” And I said: “So, what am I missing? It seems like you guys are saying there’s no way we can make it.” And she said, “You’re not missing anything. There are things we could have done in the ’80s, there are some things we could have done in the ’90s—but it’s probably too late to avoid any of the worst-case scenarios that we’re talking about.” And she literally put her hand on my shoulder and said, “I’m sorry my generation failed yours.” That was shattering to me.

TERRY: When was this?

TIM: This was in March of 2008. And I said, “You just gave a speech to four hundred people and you didn’t say anything like that. Why aren’t you telling people this?” And she said, “Oh, I don’t want to scare people into paralysis. I feel like if I told people the truth, people would just give up.” And I talked to her a couple years later, and she’s still not telling people the truth. But with me, it did the exact opposite. Once I realized that there was no hope in any sort of normal future, there’s no hope for me to have anything my parents or grandparents would have considered a normal future—of a career and a retirement and all that stuff—I realized that I have absolutely nothing to lose by fighting back. Because it was all going to be lost anyway.

DeChristopher also discussed a 2008 speech by Naomi Klein that noted that Barack Obama’s goals for climate change were centrist, that “even his pie-in-the-sky campaign promises were not enough.” “And so if the center is not good enough for our survival,” Klein argued, “and if Obama is a centrist, and will always be a centrist, then our job is to move the center.” So DeChristopher realized that “you have to go to the edge and push” :

I mean, with climate change, the center is this balancing point between the climate scientists on one side saying, “This is what needs to be done,” and ExxonMobil on the other. And so the center is always going to be less than what’s required for our survival.

Much of the conversation between DeChristopher and Williams involved the complexity of nonviolent resistance, about creating opposition without hatred. It’s easy to see what DeChristopher is fighting against – in particular the fossil-fuel interests that directly oppose action on climate change. But underlying that opposition is a wellspring of love. “This is what love looks like,” DeChristopher told the judge before receiving his prison sentence.

It took him a long time to grapple with the enormity of climate change. He dealt with despair and anger until he realized that there is great hope to be found in the traumatic change that is now inevitable for humanity:

It means that we’re going to be living through the most rapid and intense period of change that humanity has ever faced. And that’s certainly not hopeless. It means we’re going to have to build another world in the ashes of this one. And it could very easily be a better world. I have a lot of hope in my generation’s ability to build a better world in the ashes of this one. And I have very little doubt that we’ll have to. The nice thing about that is that this culture hasn’t led to happiness anyway, it hasn’t satisfied our human needs. So there’s a lot of room for improvement.

DeChristopher believes his generation can build a “humane world” that puts people’s well-being above the consumption of material goods:

I’m for a humane world. A world that values humanity. I’m for a world where we meet our emotional needs not through the consumption of material goods, but through human relationships. A world where we measure our progress not through how much stuff we produce, but through our quality of life – whether or not we’re actually promoting a higher quality of life for human beings. I don’t think we have that in any shape or form now. I mean, we have a world where, in order to place a value on human beings, we monetize it – and say that the value of a human life is $3 million if you’re an American, $100,000 if you’re an Indian, or something like that. And I’m for a world where we would say that money has value because it can make human lives better, rather than saying that money is the thing with value.