The following is a letter sent to every U.S. Senator by Everett B. Kelley, the president of the American Federation of Government Employees.

March 12, 2025

Dear Senator:

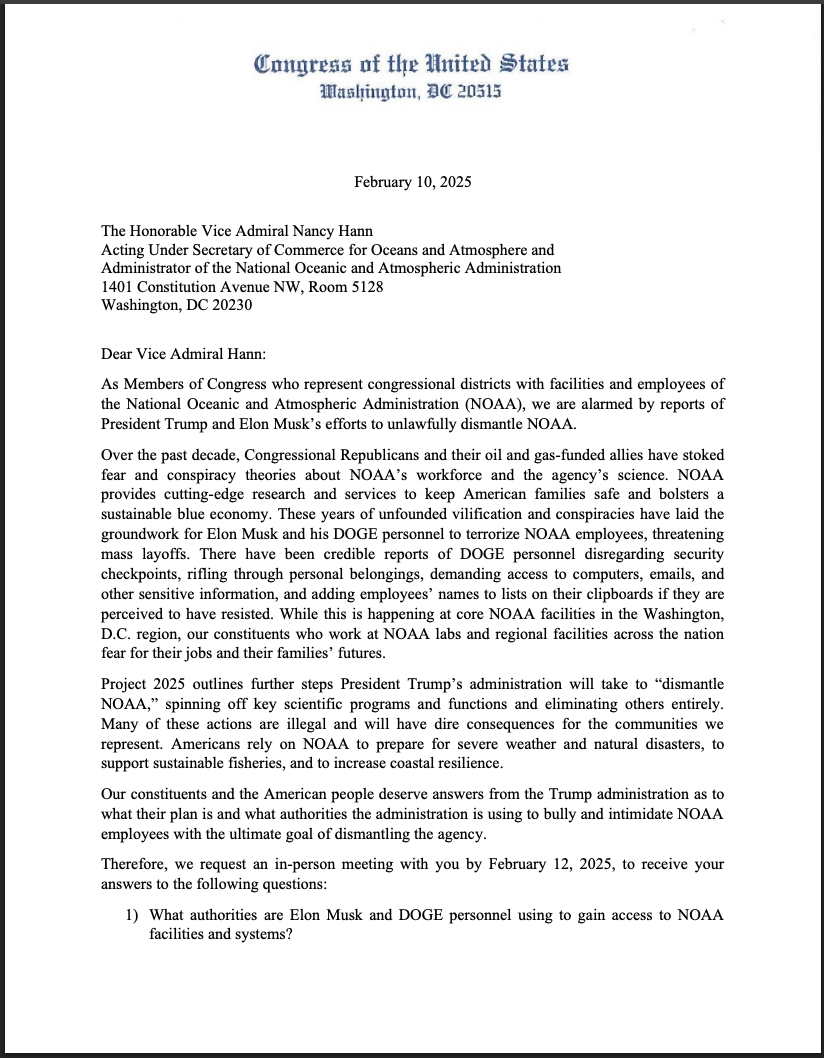

On behalf of the American Federation of Government Employees, AFL-CIO (AFGE), which represents more than 800,000 federal and D.C. workers, I strongly urge you to oppose H.R. 1968, the spending measure that the Senate will consider this week. Please vote NO. As AFGE clearly stated in its March 3 letter to Senate members, AFGE’s support for a third continuing resolution is contingent on maintaining funding for all federal programs at Fiscal Year 2024 levels and including provisions to ensure the administration spends appropriated funds as stipulated by Congress.

AFGE’s decision to oppose the spending measure is not taken lightly. AFGE’s position until this year has been that although continuing resolutions are far from ideal, they are better than an outright government shutdown. During past budget stalemates, AFGE has always reluctantly supported passage of CRs.

This year is different. Hard experience has forced AFGE to break from past practice and oppose H.R. 1968. The Trump administration has repeatedly demonstrated over the last seven weeks that it will not spend appropriated funds as the law dictates, including funds provided under the current continuing resolution that was enacted in December with AFGE’s support. Our members, and hundreds of thousands of other federal employees who benefit from our representation, are suffering as a consequence: at USAID, at the Department of Agriculture, and at the Social Security Administration, to name just three prominent agencies in the news. AFGE is particularly struck that even as the Senate prepares to debate and vote on H.R. 1968, the Trump administration has announced its intention to effectively destroy the Department of Education regardless of whether Congress approves or disapproves of that decision. How support for H.R. 1968, which under Title IX of the bill would appropriate funds to the Department, can be reconciled with the certainty that the administration will not actually spend the money as provided in law requires a suspension of logic in which AFGE refuses to participate.

As if this were not bad enough, just last week Department of Homeland Security cancelled the collective bargaining agreement with the Transportation Security Administration and declared the TSA to be union-free, citing as justification a string of outright lies designed to cast TSA employees in the worst possible light. The Department’s action stripped the workplace rights of 25,000 Transportation Security Officers who have exercised them not for the purpose of negotiating wages and benefits, which Title 5 prohibits, but simply to achieve the basic workplace rights and protections that have applied to the rest of the civil service since 1978. The nation depends on TSOs to safeguard the nation’s skies, ports, and rail systems from terrorist attacks, a job they have done admirably since 9/11. The chilling loss of rights makes one of the most difficult jobs in the country even less tenable. A vote for H.R. 1968 would, in AFGE’s view, be an expression of support for, or at best indifference toward, the administration’s campaign to openly bust labor unions. Last week’s action against TSOs is almost certainly just the first salvo in a broader campaign to destroy unions across the government, likely using national security as a pretext, and then turn to attack private sector unions as well.

We urge the defeat of any bill – including the current House Republican CR – that fails to undo the Administration’s reckless, punitive, dangerous action last week at TSA.

With thousands of federal workers either fired, placed on administrative leave, or at immediate risk of losing their jobs, AFGE members have concluded that a widespread government shutdown has been underway since January 20 and will continue to spread whether senators vote yes or no on H.R. 1968. Under the current CR, federal workers are being treated no better than they will be if government funding ceases Friday night. Yes, it is true that workers who have not yet been fired are at least drawing a paycheck – for now. But if H.R. 1968 becomes law – a measure that ignores the administration’s brazen refusal to carry out duly enacted laws of Congress and further erodes Congress’s power of the purse – AFGE knows that DOGE will dramatically expand its terminations of federal workers and double down on its campaign to make federal agencies fail because there will be nothing left to stop the Administration for the balance of Fiscal Year 2025, if ever.

Only a return to the negotiating table can prevent the government-wide debacle that we see every day. A yes vote on H.R. 1968 eliminates one of the last opportunities for Congress to assert any rights under Article I of the Constitution.

AFGE is certainly doing its part in federal court to challenge the administration’s unlawful actions against the federal workforce and will continue to do so with the same vigor it has since January 20, whether or not Congress reaches a responsible spending agreement by March 15. Deeply regrettable though a government shutdown would be, it would not impair the federal judiciary’s ability to hear AFGE’s suits or our willingness to argue them in court.

We have no doubt the administration’s refusal to follow the law will go into overdrive if H.R. 1968 becomes law, and that the more than 70 agencies for which our members work will suffer the same fate of USAID and other agencies. We question whether the bill should even be considered a “continuing resolution” given its gratuitous $1 billion cut to the District of Columbia’s budget and unjustified interference in DC’s home rule and its ability to spend its own tax revenues. The spending measure amounts to a blank check to the administration for the rest of Fiscal Year 2025 and an abdication of Congressional authority that will long outlive the debates of this week.

AFGE categorically rejects any claim that voting no on the CR is a vote for a government shutdown. First of all, Congress still has ample time to adopt a short-term CR over the weekend, if there is the will to do so. Second, we only find ourselves in the current predicament because of the Republican leadership’s steadfast refusal to engage in sincere bipartisan negotiations on this or any issue since December – a stark contrast to how Congress handled the debt ceiling crisis in 2023. Third, the minority in both chambers has proposed an actually “clean” short-term CR, which would likely easily pass in Congress if Republican leaders allowed a vote.

Thank you for your consideration of our views.

Sincerely,

Everett B. Kelley

National President

The public

mockery of “environmentalists” for concern about climate pollution began

with a The New York Times op-ed by an

The public

mockery of “environmentalists” for concern about climate pollution began

with a The New York Times op-ed by an

Readers of the New York Times

opened their papers today to a giant photo of Donald Trump appearing

above the headline “

Readers of the New York Times

opened their papers today to a giant photo of Donald Trump appearing

above the headline “